Writing Minor Key Chord Progressions

There are a lot of popular songs written in minor keys. And knowing how to write songs in both major and minor keys greatly expands your options as a songwriter.

But minor key progressions can be trickier to write than major key progressions.

So let’s take a closer look at how minor key progressions work, and some practical frameworks you can use for writing your own minor key songs.

What is a minor key?

We’ve already looked in detail at writing chord progressions in major keys. When it comes to minor keys, things are a little more complex.

In the European classical tradition, there are actually three minor scales:

- Natural minor

- Harmonic minor

- Melodic minor

In popular music, if someone tells you a song is in F minor, it’s a safe bet that it’s in F natural minor. We will be treating the natural minor scale as the default minor scale in what follows.

The natural minor scale is a mode of the major scale (called the “Aeolian mode”).

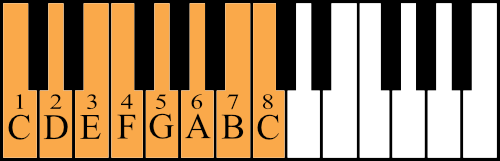

To say it’s a mode means that it uses the same notes, but starting and ending on a different “home note”. It’s easier to illustrate than describe, so take a look at the C major scale on the keyboard. Each note is numbered with its scale degree in major:

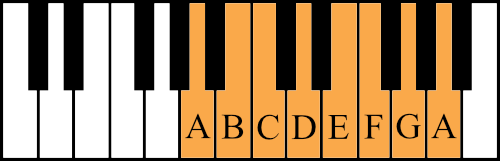

If we play these same notes starting on the 6th scale degree of major, we are playing the Aeolian mode (which is the natural minor scale):

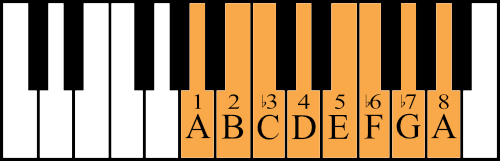

We can number these notes with the scale degrees of A natural minor:

The three distinctive notes of the natural minor scale are b3, b6, and b7.

This is easier to see if we compare two parallel scales. Parallel scales begin on the same note but are different kinds of scales.

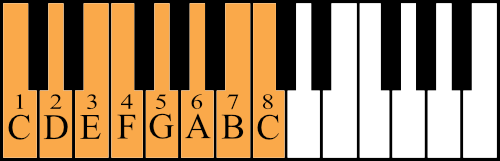

For example, C major and C natural minor are parallel scales because they both begin on C.

Notice that in C natural minor the 3rd, 6th, and 7th degrees are lowered compared to C major. That’s what b3, b6, and b7 mean:

Let’s compare on the keyboard.

Here’s C major:

And here’s C natural minor:

You can see how E, A, and B are lowered in C natural minor compared to C major (to Eb, Ab, and Bb).

If you’d like to dig deeper into scales, modes, and keys, you can check out my introduction to music theory for songwriting. But in what follows, we’ll be focusing on the chords found in a minor key.

The basic chords of natural minor

There are seven basic chords that can be built on the natural minor scale, one for each note in the scale. Here they are in C natural minor:

These can be written using Roman numeral notation, which allows us to describe chords and chord progressions in a way that applies to any key. An uppercase Roman numeral means a major chord, lowercase means minor, and ° means diminished:

Here’s a chart showing these chords in every minor key:

The i chord in minor keys is called the “tonic chord”. You can think of it as home base for the key.

Diminished chords can be difficult to use (and are relatively uncommon in popular music), so we will ignore the ii° chord for now.

We’re going to divide the other six chords in natural minor into two groups: “core” chords and “color” chords:

Core: i, iv, v

Color: bIII, bVI, bVII

The basic idea is that core chords can be used to establish the key and a sense of home and color chords can be used to add dimension and feeling.

This is definitely an oversimplification of how these chords can be used! But it’s one way to orient yourself when learning the keys. We’ll complicate this picture a little as we go.

The core chords

The core chords help us establish that we are in a minor key, and that a particular chord is home base for our song (or section).

The three core chords in natural minor are i, iv, and v. Together, these chords contain every note in the natural minor scale.

This means that, technically, any melody built on the natural minor scale can be harmonized with just those three chords.

But when songwriters actually write songs in minor (whether they realize they are doing it or not), they have two other common choices for core chords: V and IV.

As we will see, this is related to the fact that minor is a system that can go beyond just the natural minor scale.

But for now, let’s view the core minor key chords as follows:

Core: i, iv, v

Extended Core: IV, V

Let’s look at each chord one by one.

The i chord

In a minor key, the i chord is called the tonic chord. Think of this as the home chord for the key.

If we are in the key of C minor, the tonic chord is the C minor (Cm) chord. If a song sounds like it’s in minor, then the minor tonic chord will play a special role in that song.

Hearing the tonic can feel like arriving home. Leaving it behind can feel like moving outward.

But you can actually write an entire section (or even an entire song) without leaving the i at all. Here’s a static progression of that kind:

| i | i | i | i |

Ex: | Cm | Cm | Cm | Cm |

The | | symbols above indicate a single bar, which in the common 4/4 time is equal to a count of 4 beats.

The v chord

You can write an entire song on the tonic chord, but I’m sure you want to go beyond just one chord.

The next chord to consider is the v chord. It has a tendency to reinforce the i, providing a little depth, and also pulling us back in the direction of the i.

Here’s what the i and v sound like in an alternating progression:

| i | v | i | v |

Ex: | Cm | Gm | Cm | Gm |

We can heighten the pull of v to i by staying on the i for longer:

| i | i | i | v |

Ex: | Cm | Cm | Cm | Gm |

The V chord

In minor songs, there is an even stronger way to create a pull toward the tonic chord. This is by using one of our extended core chords, the V.

The V is just the major version of the v chord we’ve already seen.

One way to think of the V chord is as a borrowed chord from the harmonic minor scale. In fact, one of the reasons the harmonic minor scale developed in European classical music was to allow for the movement from V to i.

Since playing is easier than describing, let’s listen to it. Here it is in an alternating progression:

| i | V | i | V |

Ex: | Cm | G | Cm | G |

And here we emphasize the stronger pull of the V chord by dwelling on the i for longer:

| i | i | i | V |

Ex: | Cm | Cm | Cm | G |

Note that both the v and the V chord can play a “dominant function”. Think of this function as reinforcing, pulling toward, and resolving to the tonic chord.

As we explore more chords in the minor key, we’ll hear more examples of how the v and V can be used to bring us back to the i.

The iv chord

The iv chord is the first chord we’re considering that has a tendency to move away from the i.

You can often find this tendency described as the subdominant function.

Think of a subdominant chord as moving away from the tonic (the i) and toward a dominant chord. This is one way to describe the development of a song.

However, keep in mind that these concepts come from the analysis of European classical traditions. Popular music does not neatly follow these conventions!

So think of concepts like dominant and subdominant as just one way of understanding the chords in a key.

Let’s listen to the i and iv alternating to get a sense of their relationship:

| i | iv | i | iv |

Ex: | Cm | Fm | Cm | Fm |

Now that you have a feel for the iv, let’s see how it can move away from the i and toward the v. Pay attention to how the v moves us back toward the i:

| i | i | iv | v |

Ex: | Cm | Cm | Fm | Gm |

We can now contrast this with the effect of the V chord. Pay attention to whether you hear this as creating a stronger pull “back home” than the v:

| i | i | iv | V |

Ex: | Cm | Cm | Fm | G |

The IV chord

Just as with the v, we have the option to use the major version of the iv in minor songs.

You can explain the IV chord in different ways. It could come from the melodic minor scale, the third of the three minor scales mentioned above. It could be borrowed from the Dorian mode. Or it could be borrowed from the parallel major scale.

Whatever the explanation, the IV chord can provide an interesting and somewhat unexpected bright sound in a minor song.

It can also play the subdominant function described above, moving us away from the tonic i chord and toward a dominant chord (we’ve discussed v and V as examples of dominant chords in minor).

But let’s start again with an alternating progression between i and IV:

| i | IV | i | IV |

Ex: | Cm | F | Cm | F |

Standing on its own, the progression is ambiguous. It could be a song in the Dorian mode. It also sounds like the ii-V of a major key. In fact, if we ended this progression on the Bb chord, then it would definitely be a ii-V (in the key of Bb major).

The takeaway is that to get a minor key sound, you’ll need to do more than alternate i and IV. However, harmonic ambiguities like the above can also make songs more moody and mysterious, in part because it is less clear where they are going.

Let’s hear the IV in its subdominant role. Here it takes us away from the i to brighter territory, and leads back to the darker v:

| i | i | IV | v |

Ex: | Cm | Cm | F | Gm |

Contrast this same move with the V instead of the v:

| i | i | IV | V |

Ex: | Cm | Cm | F | G |

What’s interesting about this is that IV and V are the core chords of a major key. So we half-expect to hear this progression end on the major I instead of the minor i. At least to my ear, this makes the i chord following V stand out as darker than expected.

Another move to play around with is going from IV to iv. Here we use i and v to set up our key, then move out to IV. The final change to iv is a moody one:

| i | v | IV | iv |

Ex: | Cm | Gm | F | Fm |

Using that change in the middle of a progression makes it subtler:

| i | IV | iv | V |

Ex: | Cm | F | Fm | G |

Hopefully it’s becoming clear that we can do a lot of exploration with just these chords:

Core: i, v, iv

Extended: V, IV

I recommend getting a good feel for them before moving forward. Play as many combinations as you can think of, and write melodies over them. Remember to write down (and/or record) your favorite progressions.

You don’t have to play in just the key of C minor of course. Use the table above to find these chords in any minor key. For IV and V, just use the major version of the iv and v minor chords.

Color Chords

The core and extended core chords gave us a lot to experiment with. You could certainly write entire songs with just those chords.

But why stop there?

There are three more chords we’re going to explore, the bVII, the bIII, and the bVI. I’m calling these “color chords” because they can be used to add depth and feeling to a song.

The bVII chord

The first “color chord” we’ll consider is the bVII. At least to my ear, this is the least “colorful” of the three.

As always, let’s start by listening to an alternating progression:

| i | bVII | i | bVII |

Ex: | Cm | Bb | Cm | Bb |

You might hear the bVII as somehow “reinforcing” the i in this progression.

The bVII can actually play a dominant function in a minor key, pulling us toward the tonic i. It’s possible you’ll hear the transition from bVII-i as even more “final” than the more classical V-i. That’s because it’s a very common transition in popular music.

Let’s try it out that way, going from i to a subdominant to bVII and back to i. To make it a bit more interesting, I’m using both IV and iv as subdominants in order to draw out our time away from home:

| i | IV | iv | bVII |

Ex: | Cm | F | Fn | Bb |

This updates our list of minor key dominant chords to:

v, V, bVII

The bIII chord

Our next color chord is the bIII. The most important fact about this chord is that it is the tonic chord of the relative major key.

For example, the bIII in Cm is Eb. This means the relative major key for C minor is the key of Eb major. In fact, if you want to know the relative major key for any minor key, refer back to our table above and just look up the bIII chord.

bIII and the relative major key

There are a number of reasons it matters that the bIII is the tonic of the relative major. Let’s consider two.

First, one could argue that major keys are more stable than minor keys, if for no other reason than they are often treated as a default.

This means that there is a “risk” that emphasizing the bIII will cause listeners to hear our song as being in the relative major key.

This is not necessarily bad of course, but it’s worth keeping in mind.

Second, knowing this gives us an option to purposely move to the relative major key at some point in our song. For example, our verse could be in minor and our chorus in the relative major.

It is actually less common for popular songs to be entirely in a minor key than entirely in a major key. So you may find that this kind of modulation (movement between keys) produces a satisfying effect.

Examples of progressions with bIII

Keeping these points in the back of our minds, let’s look at some of the ways to use the bIII while staying in a minor key.

Again, let’s start with the alternating progression:

| i | bIII | i | bIII |

Ex: | Cm | Eb | Cm | Eb |

The i and the bIII share two notes in common. This might help explain why this alternating progression can sound like a “deepening” of the i.

The bIII can play the harmonic function of prolonging the tonic, which you can think of as keeping us grounded in that chord without literally repeating it.

On its own, the above progression is actually ambiguous between a i-bIII in minor and a vi-I in the relative major. As with the i-IV discussed above, this ambiguity can be used to create interest, but it also means we’ll need to do more to establish that we’re in minor.

Since putting the bIII in highlighted positions in the progression can make it feel like we’re in major, let’s see how to avoid this.

The two most highlighted positions in a chord progression are normally the first chord and the last chord. So to maintain a minor feel, it can be useful to keep the bIII out of those positions.

Here’s an example where we use the bIII to prolong our feeling of home before moving out to a subdominant and then to a dominant:

| i | bIII | iv | V |

Ex: | Cm | Eb | Fm | G |

The other characteristic of this progression is that it’s walking up (or ascending) through the adjacent chords bIII-iv-V. Ascending or descending progressions are common in minor key songs.

What happens if we move out to a subdominant but then go to bIII before a dominant? Let’s try it:

| i | iv | bIII | bVII |

Ex: | Cm | Fn | Eb | Bb |

We’re starting to hear some more varied colors in the same progression. And at least to me, the bIII in this progression sounds a bit like an altered echo of the initial i.

Finally, we’ve been using a lot of examples relying on harmonic functions (tonic, subdominant, and dominant), but you should not think of these as rules you need to follow. Harmonic functions is just one technique you can use to structure your progressions.

Here’s an example that ignores these functions:

| i | bVII | bIII | iv |

Ex: | Cm | Bb | Eb | Fm |

Remember, what matters is how the song sounds, not whether it follows some rules from music theory.

The bVI chord

The last chord we’ll be considering in this post is the bVI chord. At least to my ear, this is the most colorful of the color chords considered here.

Let’s hear it alternating with the i:

| i | bVI | i | bVI |

Ex: | Cm | Ab | Cm | Ab |

The bVI can be considered another subdominant chord. Note that it shares two notes in common with the subdominant iv chord.

In the guise of a subdominant chord, we can think of it as moving us away from the tonic (and toward a dominant). Based on these ideas, we might consider a very common minor key progression:

| i | i | bVI | bVII |

Ex: | Cm | Cm | Ab | Bb |

The movement of bVI-bVII-i signals we’re in a minor key. Let’s explore a couple of other ways to make use of this movement.

First, let’s make a relatively small change, dwelling on the bVII at the end instead of the i at the beginning:

| i | bVI | bVII | bVII |

Ex: | Cm | Ab | Bb | Bb |

This illustrates that even small changes like this have a significant impact on the role of each chord in the progression. Dwelling on the i made it sound like bVI-bVII was a temporary movement away from it. Dwelling on the bVII makes it sound like i-bVI is a temporary movement toward the bVII.

Next, let’s try an even more significant change, starting our progression on bVI and moving toward the i:

| bVI | bVII | i | i |

Ex: | Ab | Bb | Cm | Cm |

One interesting aspect of this progression is that bVI-bVII could also be a IV-V in the relative major. This makes the arrival of the i potentially more interesting, precisely because we at least somehow expect the bIII instead.

To better understand this, listen to the following progression:

| bVI | bVII | bIII | bIII |

Ex: | Ab | Bb | Eb | Eb |

Though we’re notating these chords with minor key Roman numerals, this is unambiguously a IV-V-I in the key of Eb major (our relative major).

For this reason, if you really want a section to be in minor, it’s probably best not to use bIII, bVI, and bVII together in that same section.

You can explore all kinds of ascending and descending progressions using the bVI. For example, the ascending iv-v-bVI and the descending bVII-bVI-v:

| iv | v | bVI | i |

Ex: | Fm | Gm | Ab | Cm |

| bVII | bVI | v | i |

Ex: | Bb | Eb | Gm | Cm |

There is huge space for exploration here. We’re just scratching the surface.

How to emphasize the minor key

Those are all of the chords we’ll be discussing in this post. They provide us with enough options to generate countless songs.

With all of this information in mind, it’s worth returning to the “problem” of harmonic ambiguity.

[Note: This section gets a bit more technical as we discuss the relationship between natural minor and its relative major. Feel free to skip to the next section if it’s too much theory. The TL;DR version is that using V or IV in a minor key can make it clear that we’re not in the relative major.]

Some progressions are clearly in a major key. Some are clearly in a minor key. And some are ambiguous between major and minor.

There are definitely other possibilities than these, but we’re ignoring them for purposes of this post.

If you are playing freely with chords, you might easily land on an ambiguous progression. Whether this is good or bad depends on what you’re trying to do.

As mentioned above, ambiguous progressions can create mystery, uncertainty, and harmonic interest. On the other hand, of course, they can also be boring.

Either way, keep in mind that ambiguous natural minor progressions often lean toward major.

To understand how, let’s look at the chords in natural minor, and how they correspond to the chords in the relative major. I’m using the chords in the key of C minor (and its relative major the key of Eb major) as examples:

Any progression that uses only natural minor chords could in theory be interpreted as being in the relative major (using the corresponding major key Roman numerals listed above).

For example, consider this natural minor progression in C minor:

| i | bVI | bVII |

| Cm | Ab | Bb |

This could be interpreted as a progression in the relative major key of Eb major:

| vi | IV | V |

| Cm | Ab | Bb |

Whether this is “correct” depends on a lot of factors, and is often a matter of opinion. As songwriters, we shouldn’t care so much about what’s “correct”, but instead about how the song sounds.

If you want to capture a “minor feel”, but find that your songs keep slipping into a major feel, there are a few things you can do.

First, the V-i is one way to unambiguously demonstrate you are in minor. That’s because V-i is common in minor songs, but the III chord is rare in major songs (the V in minor is the III in the relative major).

So throwing in a V can be enough to do the trick.

This is perhaps even more important in 4 chord progressions where each chord is given equal weight. If such a progression includes both a i and a bIII, then it could probably also be interpreted as a major progression (using a vi and I in the relative major).

You can play with some of these ambiguities while still maintaining a minor feel by using V and v in different sections of your song (but not in the same section). That’s because the sections with v instead of V will potentially be more harmonically ambiguous.

We’ve already looked at the bVI-bVII-i progression. This is a common minor progression, but it’s also a common deceptive cadence in the relative major.

A deceptive cadence is where you set up a common return home but go somewhere else instead. If we interpret bVI-bVII-i as a IV-V-vi in the relative major, then we get a pretty common deceptive cadence.

Here are two ways to set up the bVI-bVII-i that make it pretty clear we’re not in the relative major:

| V | bVI | bVII | i |

Ex: | G | Ab | Bb | Cm |

| IV | bVI | bVII | i |

Ex: | F | Ab | Bb | Cm |

We’ve already discussed why the V makes it clear we’re in minor. The IV can also have this effect. That’s because it would be a II in the relative major, and the II is uncommon in major keys.

The II is a common chord in the Lydian mode, which is one of the major modes. But the most distinctive fact about the Lydian mode is that it doesn’t have a IV chord. And our minor key bVI chord would be the IV chord in Lydian (if our minor key IV chord is interpreted as the Lydian II).

If all this is going over your head, don’t worry! The important takeaway is that both IV and V can be used in minor key songs to establish more clearly that we are in a minor (and not a relative major) key.

Frameworks for writing progressions

We have looked at eight chords for use in minor key progressions, broken down in two ways. First as core, extended core, and color chords:

Core: i, iv, v

Extended: IV, V

Color: bIII, bVI, bVII

In this way of looking at things, the core and extended core chords establish the key and a sense of home, and the color chords add depth and feeling.

Second, we’ve considered our eight chords in terms of harmonic functions:

Tonic: i, [bIII]

Subdominant: iv, IV, bVI

Dominant: v, V, bVII

In this way of looking at things, i is our home chord (and bIII can be used to prolong it, which is why I placed it in brackets). Subdominant chords move us away from home and toward dominant chords. And dominant chords pull us back home.

Both of these ways of looking at our chords are frameworks for approaching songwriting. By a framework, I mean a way of thinking about the relationship between chords that narrows your choices and helps you find combinations that sound right.

Even the idea of a minor key is a framework in this sense.

There are endless possibilities when it comes to songwriting. Learning and experimenting with frameworks is one way to bring this huge space of possibilities under control.

Just don’t mistake a framework for an ironclad set of rules.

With that caveat in mind, it’s now time to try out these frameworks and see what kinds of songs you can discover by using them!