The Super Key: Beyond Major and Minor Keys

You might be familiar with major and minor keys. Maybe you’ve tried to write songs in these keys.

But when it comes to popular music, many songs are not easily categorized as being in either one!

There’s a world beyond major and minor, and it can really open up possibilities for your songwriting.

In this post, we’re going to explore one interesting way to move beyond major and minor: mixing them together into one super key! There are plenty of other ways to do it, but this gives us a nice starting point for discovering new approaches to writing chord progressions.

Think of the major key as a foundation

What’s nice about thinking in terms of a major key or a minor key is that you have a handy list of notes and chords that are likely to at least sound “correct”. And these concepts can help you build out foundations for thinking about and improvising chord progressions.

So let’s start with a quick review of what it means to write a chord progression in a particular key. Let’s take that old classic, the key of C major.

To say we’re in C major means that we’re using a major scale that begins on the note C. Major scales have a particular pattern of whole (W) and half (H) steps: W-W-H-W-W-W-H.

In C major, that scale consists of all the white notes on a piano (beginning and ending on C):

We can start a triad (3-note chord) on each note in a scale by sticking to notes in that scale (skipping as we go). For example, the C major chord is C-E-G:

And the D minor chord is D-F-A:

Each of these chords can be represented by a Roman numeral (uppercase for major, lowercase for minor). Here they are for the C major scale:

C Major: C - Dm - Em - F - G - Am - Bdim

I - ii - iii - IV - V - vi - vii°

The Roman numeral system tells us information about chords that is not bound to any particular key. For example, if we take the key of A major instead, we get:

A Major: A - Bm - C#m - D - E - F#m - G#dim

I - ii - iii - IV - V - vi - vii°

You can use tables (for example, from my songwriting cheat sheet↗(opens in a new tab)) to transpose Roman numeral chord progressions to any key.

By the way, that ° symbol means “diminished”. Diminished chords are pretty rare in popular music and they’re difficult to use well. So though I’ve listed them for completeness, let’s just ignore them for now.

This means that when writing in a major key, you have 6 chords to work with:

I, ii, iii, IV, V, vi

We can further divide these chords into two groups, what I will call the “core” chords and the “color” chords:

Core: I, IV, V Color: ii, iii, vi

The core chords most strongly establish a sense of home in a key. You can write whole songs just using I, IV, and V. The standard blues progression, for example, consists of just these chords, and so do many folks song progressions.

So a good place to start when exploring the major keys is to restrict yourself to these chords.

But this can be pretty limiting. The color chords above give us more options to explore.

My post on writing major key chord progressions describes all of these chords in more detail.

For now, one very simplistic (but still useful) way to look at it is that the core chords establish a sense of home in your key and the color chords add feeling and depth. Playing around with this idea is one effective way to practice writing songs.

Explore the minor key

The minor key is actually more complex than the major, but for our purposes we will keep it simple, focusing on what is called the “Aeolian mode” (or “natural minor”). The Aeolian mode is just a scale that starts and ends on the 6th note of the major scale.

Take the C major scale again:

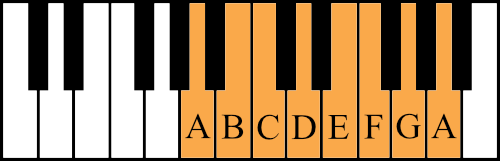

If we take these same notes but start and end on the 6th note (which is A), we get a “mode” of C major:

Note that this is the same exact collection of notes (in this case the white keys on the piano) but in a different order. If we form triads as we did before, but this time using the notes in this order, we get the following chords:

A minor: Am - Bdim - C - Dm - Em - F - G

i - ii° - bIII - iv - v - bVI - bVII

Notice that these are also the same exact chords as in C major, again just in a different order. But now we start the Roman numeral numbering on Am, represented as the lowercase (minor) i.

You might be wondering why we have bIII, bVI, and bVII instead of III, VI, and VII. That’s because, compared to A major, the root notes of these chords are one half step lower. Let’s see that comparison, focusing just on the notes in the A major and A natural minor scales:

A major: A - B - C# - D - E - F# - G#

| | |

v v v

A minor: A - B - C - D - E - F - G

You can see that the 3rd, 6th, and 7th notes are sharp in A major but not in A minor. Another way to say that is that these notes are flat in A minor compared to A major.

Let’s see that comparison again, but this time with the C major and C natural minor scales:

C major: C - D - E - F - G - A - B

| | |

v v v

C minor: C - D - Eb - F - G - Ab - Bb

Again, the 3rd, 6th, and 7th notes are flat in C minor but not in C major. And that’s why we get bIII, bVI, and bVII.

For completeness, here are the chords in the C minor scale:

C minor: Cm - Ddim - Eb - Fm - Gm - Ab - Bb

i - ii° - bIII - iv - v - bVI - bVII

Relating major and minor: derivative and parallel approaches

We have just explored two ways of thinking about the relationship between major and minor. The first approach, sometimes called the derivative approach, compares a relative major and relative minor.

For example, the key of A minor is the relative minor of C major because it consists of the same notes and chords but in a different order.

The second approach, sometimes called the parallel approach, compares the major and minor keys for the same root note.

For example, C major and C minor are parallel major and minor keys.

In the rest of this post, we will focus on the parallel approach. This is because we ultimately want to combine the major and minor keys starting on the same note into one super key!

Core and color chords in minor

Just as we had core and color chords in major, we have core and color in minor:

Core: i, iv, v Color: bIII, bVI, bVII

Notice that we are ignoring the diminished chord again (in the case of minor, the ii°). It’s worth noting that the ii° is not as uncommon in popular music, particularly in the form of the related ii7b5 chord. But we’ll still leave it aside for now.

You can view these chord groups the same (simplistic) way we did before. The core chords establish and sustain the key, whereas the color chords add feeling and depth.

One difference here is that in minor you can also borrow the V chord from what’s called the “harmonic minor” to create a stronger sense of returning home. This is a common technique in minor songs.

My post on writing minor key chord progressions describes all of these chords (and a couple more) in greater detail.

The super key: beyond thinking in major and minor

Now that you have a basic grasp of the major and minor keys, it’s time to explore moving beyond them. To start with, let’s look at both lists of chords:

Major: I - ii - iii - IV - V - vi - vii° Minor: i - ii° - bIII - iv - v - bVI - bVII

One interesting idea is to treat all of these chords as forming a larger “super key”. This generates a new list of core and color chords:

Core: I, IV, V, i, iv, v Color: ii, iii, vi, bIII, bVI, bVII

So in practice how do we write songs in this super key?

Borrowing chords vs. mixing core and color chords

The easiest way to start is to choose mostly chords from the major or minor side, and borrow one or two from the other side. These borrowed chords will create an unexpected sound, and can really make that part of a song stand out.

I go into more detail about how to borrow chords here.

Another way to approach mixing major and minor is to use some of the core chords (possibly from both) to create a sense of home. Then pick a couple of the color chords to add depth to that.

This will require more experimentation, and can be difficult to get right at first. But if you persist, you’ll probably discover chord progressions you would never have thought of if you had just relied on your old habits.

I recommend you start from the borrowing mindset, mostly sticking to major or minor. This will give you a feel for how you can break out.

Once you have that down, you can explore the mixed core and color approach. This will probably provide an endless world of songs to discover.

Experimenting with collections of chords

Before we finish, let’s explore one more technique.

Start by picking a home chord, either I or i. Then, without thinking too much about it, pick any collection of other chords from our lists above.

Experiment with putting those chords in different orders until you find a progression that sounds “right”. Don’t be afraid to keep starting over with a new collection of chords.

The idea is to explore the possibilities, not to get caught up in using a particular group of chords successfully.

And remember that a song can actually contain both the I and i chords!

These techniques can make it harder to improvise melodies

I will note that improvising melodies over these “super key” chord progressions can be a lot more challenging than improvising melodies over either major or minor progressions.

That’s because, whether you know it or not, you’ve probably deeply internalized the major and minor scales from hearing them used so many times in so many ways. The mixture creates more interesting possibilities, but this comes with greater difficulty from lack of familiarity.

This is another reason why it’s easier to start by borrowing one chord and gradually expanding from there.

If you keep practicing, though, you can start to learn new ways of writing melodies and thinking about chord progressions. And I’m guessing you’ll come up with songs you’d never have written by relying on your old habits.